Friday, May 6, 2016

HB2: probably not over in November

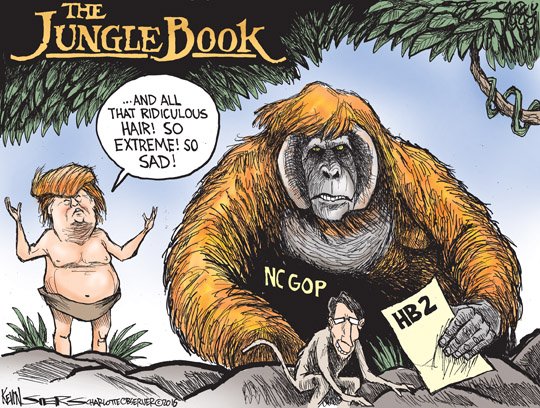

What will it take for the HB2 boycott to force a change of course in North Carolina? For one, it will mean digging in for the long haul. From Montgomery to Johannesburg, many of history's most iconic boycotts have taken years, and sometimes decades, to bear fruit.

In 1986, the state of Arizona became a boycott target after it refused to honor the federal holiday for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Growing economic losses — and the stigma of artists refusing to play in the state, from the Doobie Brothers to Public Enemy (who released the scathing "By the Time I Get to Arizona" in 1991), Stevie Wonder to U2 — pushed the issue to the forefront of the political debate. A breaking point came in 1990, when the NFL cancelled plans to host the 1993 Super Bowl in Tempe, costing the state nearly $200 million. The state enacted a King holiday in 1992, six years after the boycott started.

While corporations bring undeniable economic clout, they're often unreliable allies. As a Facing South/Institute report by Alex Kotch was the first to expose, many of the companies who have gone on record to oppose HB2 have also poured political contributions into the Republican Governors Association and Republican State Leadership Committee, groups that helped elect North Carolina lawmakers behind the law (and similar anti-LGBT legislation in Mississippi). Follow-up reports from BuzzFeed and The Huffington Post indicate these companies don't intend to stop contributing to these committees.

That drives home another lesson from successful boycott efforts: the need for social justice groups and movements to be at the center of any boycott campaign. In South Africa, the ANC adamantly supported sanctions — despite the resulting hardship it caused in black communities — and saw the value of mobilizing economic pressure through divestment campaigns. But they were clear that it was just a tool in a larger strategy aimed at changing the country's political leadership.

That leadership from North Carolina organizers and advocates on the ground will be especially important as concerns about the boycott's mounting economic cost — the very quality that makes a boycott a potentially powerful tool — continues to grow.

As Jillian Johnson, a newly-elected member of the Durham City Council and "queer North Carolinian who is committed to social justice," wrote recently, it will be up to those who oppose HB2 to explain how a boycott can be an important part of the strategy for change:

Boycotts are a highly effective nonviolent tool of political and social resistance, and in this case they are doing exactly what they were designed for: putting pressure on our elected officials to repeal this terrible legislation. Unfortunately for us North Carolinians who don’t support this legislation or those in office who created it, we are caught in the middle of this fight and face the potential for real harm based on the actions of our elected leaders. This unfortunate position (among other things) is motivating us to do exactly what boycott proponents want us to do: rail against our elected leaders about the harm they are causing us with this backwards legislation and demand that they make things right by repealing HB2. Their actions are creating the environment of public disapproval and pressure that is needed to get this legislation repealed.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment