Decades ago, when I was still a teenager in Alabama, I heard my grandmother refer to some new neighbors as the Tallyho Boys. Turns out a gay couple had bought or inherited a farm just down the road from her. The good ladies of that rural community welcomed the couple with poundcakes and homemade jelly, but would they have voted for a political candidate who supported marriage equality? Not a chance.

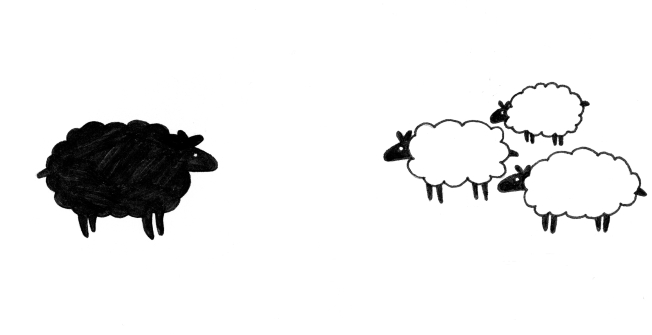

Partly this divide comes down to scale: You can love a human being and still fear the group that person belongs to.This struck me forcefully when I read it. It summed up my experience at my mother's memorial service, on the farm where she was born, in February.

I was told she died the day it happened. A few days later I was told when the service would be. I heard nothing else for a fortnight, until the day before. Then some family arrived to let me travel with them. I listened to the radio in the back seat, the rear window speakers being loud enough to make it impossible to follow, or participate in, conversation up front.

We arrived late the afternoon before. Mostly I was ignored. No one told me the timing or the arrangements. Not wishing to be provocative, I didn't ask anything; I waited to be told.

I walked around the farm a lot on my own.

Relatives began arriving for the day. Most said hello and went off to find someone else to talk with. The serious shunners did what they did best. The sort described by Renkl went through the funeral pro formas with me.

One aunt and uncle, their kids, and one other cousin actually spent time visiting with me among the family. There was no time for me to visit with my own siblings. They were busy with arrangements and visiting with others.

I had some very nice chats with strangers, who didn't know how they were supposed to react to me.

It became increasingly apparent I was irrelevant. The conversations I stood in on, I realized I'd been uninvited from family gatherings so long, I had no idea who or what my relatives were talking about. I learned one to my siblings had another marriage and divorce I hadn't heard about, from the one who told me, years ago, "Well, you can do whatever you like, just don't ask me to call it marriage."

She is trailing in the family standings, 3-2. I remain a non-starter.

A couple of cousins said they hoped to stay in touch, without asking, or offering, how to do so. Photos were taken of family groups, including my and my siblings. No one has sent me any.

But, like Renkl's neighbors, they gave me a big plate of barbecue to take home.

I was dropped off at home and all I have heard since is that the will has been filed for probate. That confirmed, in my mind, what I have long expected would be the last word from my mother: none at all.

The New York Times: The Passion of Southern Christians

Margaret Renkl

April 9, 2017

NASHVILLE — In the world of apostolic betrayals, it’s Judas who gets the headlines, but the everyday believer is more apt to fall in line behind Peter. Coldly handing Jesus over to his death in exchange for 30 pieces of silver was an over-the-top, cartoon-level move, but Peter’s terrified denial of the man he believed to be the savior of the world? That one seems immensely human to me.

I have a lot of sympathy for Peter these days. Here it is nearly Easter, and for the first time in my life I don’t want anyone to know I’m a believer. To many, “Christian” has become synonymous with angry white voters in red hats, personally responsible for handcuffing all those undocumented mothers and wrenching them out of their sobbing children’s arms.

A good number of Southern Christians tend to vote Republican, but in truth the values of the rural South are not incompatible with the policies of the Democratic Party. Our famed Southern hospitality is just an illustration of Jesus’ exhortation to welcome the stranger. And consider what happens here whenever there’s a flood or a tornado: Long before the government agencies mobilize, local churches are taking up donations, cooking hot meals, helping people pick through the wreckage — helping everyone, no matter their religion or the color of their skin or the language they speak at home.

But as with a lot of people, including secular liberals, the way Christians behave as human beings can be completely at odds with the way they vote. Decades ago, when I was still a teenager in Alabama, I heard my grandmother refer to some new neighbors as the Tallyho Boys. Turns out a gay couple had bought or inherited a farm just down the road from her. The good ladies of that rural community welcomed the couple with poundcakes and homemade jelly, but would they have voted for a political candidate who supported marriage equality? Not a chance.

Partly this divide comes down to scale: You can love a human being and still fear the group that person belongs to. A friend of mine recently joined a continuing-ed class made up about equally of native-born Americans and immigrants. The two groups integrate seamlessly, joking around like any co-workers, but the day after the election my friend said, “I think half my class might’ve just voted to deport the other half.”

Tribal bonds have always been a challenge for our species. What’s new is how baldly the 2016 election exposed the collision between basic Christian values and Republican Party loyalty. By any conceivable definition, the sitting president of the United States is the utter antithesis of Christian values — a misogynist who disdains refugees, persecutes immigrants, condones torture and is energetically working to dismantle the safety net that protects our most vulnerable neighbors. Watching Christians put him in the White House has completely broken my heart.

My husband and I are cradle Catholics, but my husband’s aunt used to refer to us as “cafeteria Catholics,” picking and choosing what we believe. Belonging to a community, feeling at home in the liturgy, carrying on a long family tradition — all these intangibles made it easy enough, before the election, to ignore much of what the church gets wrong and concentrate on what it gets right: supporting open immigration, welcoming refugees, opposing capital punishment, housing the homeless, feeding the hungry, caring for the sick and the aged and the lonely. Jesus said, “Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.” All the rest is window dressing.

But this is the part of Christ’s message that most conservative Christians ignore when they step into the voting booth. In part that’s because abortion has become the ultimate border wall for Southern believers. I can’t count the number of Christians I know who are one-plank voters: They’d put Vladimir Putin in the White House if he promised to overturn Roe v. Wade. To someone who ardently believes abortion is murder, that idea is not as crazy as it seems. But reasonable people can disagree on the moment when human life begins, and I don’t see my own commitment to protecting a woman’s legal right to choose as a contradiction of my religious practice. No matter how you define it, protecting human life should never stop at the zygote.

Republicans now have what they’ve long wanted: the chance to turn this into a Christian nation. But what’s being planned in Washington will hit my fellow Southerners harder than almost anyone else. Where are the immigrants? Mostly in the South. Which states execute more prisoners? The Southern states. Which region has the highest poverty rates? The South. Where are you most likely to drink poisoned water? Right here in the South. Where is affordable health care hardest to find? You guessed it. My people are among the least prepared to survive a Trump presidency, but the “Christian” president they elected is about to demonstrate exactly what betrayal really looks like — and for a lot more than 30 pieces of silver.

Liberal Christians in the South are by definition a lonely bunch, different from conservative Christians at home and different from secular liberals everywhere else. Still, I have never felt lonelier than I feel in Donald Trump’s America.

But I also believe in resurrection. Every day brings word of a new Trump-inflicted human-rights calamity, and every day a resistance is growing that I would not have imagined possible, a coalition of people on the left and the right who have never before seen themselves as allies. In working together, I hope we’ll end up with something that looks a lot like a Christian nation — not in doctrine but in practice, caring for the least among us and loving our neighbors as ourselves.

Margaret Renkl is a contributing opinion writer.

No comments:

Post a Comment