Werner Doehner was a boy of eight, his father a German pharmaceutical sales rep in Mexico. Doehner, his parents, and two siblings were returning from a trip to German on the first North Atlantic crossing of the 1937 season for the world's largest airship, the 803-foot dirigible Hindenburg.

The vessel, in service just fourteen months, had done so well on its twenty crossings- carrying almost 3000 passengers and 160 tons of mail and freight- there were plans to expand the Zeppelin company's fleet.

The Hindenberg was luxury travel: the five-member Doehner family paid $2000 for the crossing- some $34,500 in 2016 funds. On arrival at Lakehurst, they planned to fly to Newark and there catch the train home to Mexico City.

Zeppelin PR reps heavily promoted the arrival at Lakehurst, New Jersey, and among the large press corps was a two-man team from Chicago's WLS radio. Herbert O. Morrison, a 31-year-old Pennsylvania native stepped out of the mists of history for one minute and twenty seconds to report the last of a string of disasters that dogged the airship industry for a decade and a half.

Once the still-unsourced explosion occurred, it took 34 seconds for the Hindenburg to collapse in cinders and metal framing. "“Suddenly the air was on fire,” Doehner recalled.

His father and sister were among the sixteen passengers, 22 crew and one ground crew member who perished. Doehner and his mother were hospitalized for several months for treatment of burns and other injuries.

The 80th anniversary is being celebrated with a round of events at the former naval air station where the Hindenburg crashed. A dinner last night included many passengers of the airship's crossings, including Anne Springs Close, 90, of Fort Mill, South Carolina:

The Rock Hill Herald reports,

It’s 1937. Her father, Elliott White Springs, sits in his Fort Mill living room entertaining a German he fought as a flying ace in World War I. A young Anne Springs Close runs in from the nursery, having just heard news on the radio.

The Hindenburg exploded.

"I can remember running into the den to tell my mother and father this terrible news,” said Close, who is headed to the would-be landing spot in Lakehurst, N.J., for an 80th anniversary event Friday. “That's how they heard about it."

Close wasn’t invited for her newsbreaking. Organizers reached out because she is one of the last living links to the infamous lighter-than-air craft.

“They invited me because there are maybe three people alive who crossed the ocean on the Hindenburg,” Close said. “Yes, it's very exclusive.”

Only about 1,000 people crossed the Atlantic Ocean safely on less than a dozen trips the summer of 1936. Close’s father flew over in July that year.

“He cabled my mother and said ‘it’s perfectly safe, send the children,’” Close recalls. “So much for that.”

The family punched tickets. Close, then 10, and her brother Sonny joined their mother Frances Ley Springs, their German nanny and the nanny’s brother. Close’s mother made news as passenger No. 1,000 to cross the ocean. The Sept. 18, 1936 New York Times noted the special duralumin tray she received to honor the milestone. And the record 132 people who boarded the Hindenburg’s eighth transatlantic trip.

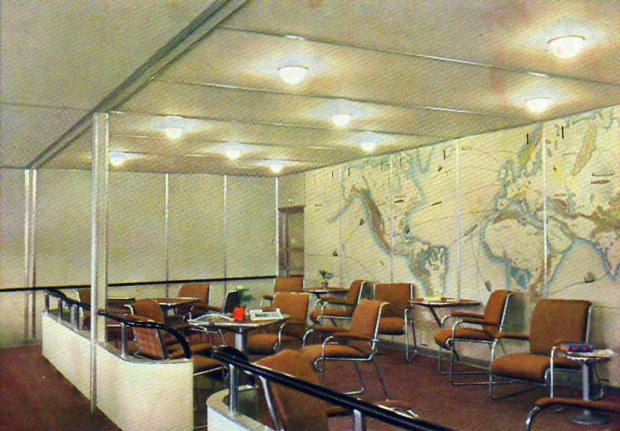

“Ten years old, you remember pretty much,” Close said. “I remember it was pretty crowded and not much to do. Not much room to move around. You were down in the gondola. I remember the slanted windows.”

Those slanted windows, which brought in more sunlight than traditional ones, so impressed Close’s father that he mimicked the design with the Springs Industries building in Fort Mill that served as a major economic catalyst for the town during the 20th century.

Natural light is a bit of a family tradition. Close provided plenty of it when she set aside 2,100 acres for the Fort Mill greenway bearing her name that opened 22 years ago.

Back in 1936, though, Close was just one of the two children on a zeppelin gondola largely filled with German businessmen. World War I was a recent memory. World War II, a coming crisis.

“Americans weren't traveling too much to Germany,” Close said.

Memories from her trip are reminiscent of the times. Apart from jigsaw puzzles there was little to do but watch ships on the sea below, growing bigger or smaller depending on the Hindenburg’s lifts and lulls with the weather.

“It's speed depended upon the air current,” Close said. “The height varied and the size of the ships varied depending on how high you were.”

Crew were “paranoid about fire, of course,” Close said. Cigarettes, pipes, cigars and anything to light them had to go to a special attendant for placement in a special box.

“If you wanted to smoke, you had to go to him,” Close said. “You had to go in what looked like a big metal telephone booth. I tell people that when we do a history event and the children don’t know what I’m talking about. I have to explain what a telephone booth was.”

Close has had plenty of time to prepare her accounts. She often tells of her connection to Hindenburg history, though she didn’t for several decades after her first and only passage.

“You didn't talk about Germany or having been there,” Close said of post-World War II America. “It was sort of taboo.”

Years later she remodeled the iconic Fort Mill home where she first broke the news to her father – the White Homestead appears on the National Register of Historic Places for having housed the last Confederate cabinet meeting – and a picture emerged linking the family to the Hindenburg.

Close can’t recall she “ever mentioned or ever thought about” her trip on the Hindenburg for several decades before people starting asking about the picture.

“I would tell them, and they were very interested,” she said.

Ann Evans, historian for the family estate, is one of many people to awe at the Hindenburg connection.

“When I came to work here in 1994, I saw the collage of their Hindenburg trip hanging on the game room wall and the 1,000th passenger plaque propped up in the bookcase,” Evans recalls. “Yes, I was amazed to be able to see and touch a real part of history.”

Evans processed and cataloged a collection, including telegrams between Close’s parents, brochures and booklets telling people what to expect and how to pack.Ceremonies at Lakehurst today will include remarks by Horst Schimer, 85, whose father designed the vessel, taking his son along on a trial voyage. Incongruously, wreaths will also be presented honoring US service members killed in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Morrison was employed as a news reporter for WLS, a large AM radio station affiliated with NBC News, in Chicago, Illinois. Because radio technology was relatively primitive in the 1930s, radio broadcasts were either aired live or not at all. WLS reluctantly allowed Morrison to go to New Jersey to experiment with new recording technology that allowed audio reports to be aired at a later date. On Thursday, May 6, 1937, Morrison and his partner Charles Nehlsen, a recording engineer, were in Lakehurst, New Jersey to report on the arrival of the German zeppelin, the Hindenburg, on her maiden voyage.

Running several hours behind schedule, the Hindenburg appeared over Lakehurst around 7:30 p.m. Many years later in an interview with Julia Martinez, a reporter for the Los Angeles Times, Morrison recalled, “It was getting dark and a little drizzle of rain had started. The landing crew was spread out around the landing strip. We could see the Hindenburg coming in and down and down and down. About ten minutes out, I started talking into the microphone.” At the time everything seemed to be going as planned. “I was talking about what it meant to the United States to have this connection with Germany and how it showed the success of air travel. I hardly had the words out of my mouth when-wow-I heard an explosion.” Morrison recalled the event, saying, “People around me gasped. They started crying and screaming. We could see things falling out of the Hindenburg… Some of the things were people.”

During the forty-two minute broadcast, Morrison’s demeanor quickly changed from one of awe and inspiration to one of horror. He began poetically, “Toward us, like a great feather…It is practically standing still now…the back motors are holding to just enough to keep it…” And then, horrified, he exclaims “…it’s bursting into flame! This is terrible! One of the worst catastrophes in the world! The flames are 500 feet into the sky!” Morrison continued, “Oh, the humanity . . . all the passengers . . . I don’t believe . . . I can’t even talk to people whose friends are on there. . . . It’s a, it’s a . . . I can’t talk, ladies and gentlemen. Honest, it just lays there, a mass of smoking wreckage.” This is most significant because Morrison was the only broadcast reporter on the scene to cover the arrival of the zeppelin. Additionally, Morrison was relying solely on instinct at the time, as there had been no precedents or standards for unscripted news broadcasts. According to a later account, Morrison was broadcasting in New Jersey at the invitation of American Airlines as a publicity stunt. Whether this is true or not, he was definitely in the right place at the right time. He became famous for his broadcast that day.

The tapes of the tragedy were items of great value to other curious reporters as well as an even more concerned group of Nazi agents in the United States. A future friend of Morrison’s would have this to say:

"I thought the most interesting thing he ever told me was that following the Hindenburg crash, a number of ‘brown shirts’ from Nazi Germany followed him on his train back to Chicago from New Jersey. They wanted to take the recording he made so that it would not be broadcast and embarrass Germany. Somehow, he found out about their pursuit and managed to evade them by staying with crowds of people on the train all the way back to Chicago. The recording was broadcast the day after the crash."

In the years following the explosion of the Hindenburg, Morrison held several different jobs in assorted radio and television stations in Pittsburgh. We can be sure that his work after the disaster was never as interesting as the events that unfolded that fateful day, but we do know that Morrison loved his work in broadcasting, and he continued for many years. For the next few decades, he worked in Pittsburgh for radio stations such as KQV, WJAS, WCAE and for WTAE-TV. In 1958, he was named the television station WTAE’s first news director.

“He talked about [the Hindenburg] once in a while,” said Charles McGrath, 64, a cinematographer at WTAE while Morrison served as a news director at the station. “What struck me about him and that incident is he never got over it. He was beside himself on that recording. I think it always stayed with him. It followed him all his life.”

After moving to Morgantown, West Virginia - his wife’s hometown - in 1970, he was often called upon to remember his famous broadcast for news outlets, especially on significant anniversaries of the event.

He also involved himself with West Virginia University where he lectured and helped develop a radio and television program for the University Relations department at WVU. Charles Cremer, a journalism professor at West Virginia University invited Morrison into his classroom many times is the 1970s. “I would play the recording of the Hindenburg radio program for my class and then he would embellish it. He was modest and humble. He understood it could have been anyone behind that microphone and thought he owed it to the world to make his story known whenever he was asked. He never seemed to tire of telling his story.”Morrison's broadcast became internationally famous in the 1950s as CBS' Edward R. Murrow's "See It Now" program unearthed the visual history of the 20th century. His most famous line- "Oh, the humanity!" has become a part of pop culture for what seems its operatic over-the-topness almost a century later.

The TV series WKRP in Cincinnati parodied it in Les Nessman's infamous Turkey Drop Broadcast; episodes of The Simpsons (“Lisa the Beauty Queen”) and South Park (“The Simpsons Already Did It”) mined it to hilarious effect.

The high-pitched, frantic quality of his reporting has since been attributed to the faster-then-normal recording speed of the equipment used; the video/audio clip here has been adjusted to present Morrison's normal speaking voice:

Morrison did a promotional tour for Universal Studios' 1975 disaster/conspiracy movie Hindenburg ("One gasbag meets another," New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael sniffed), which used his recording but cast actor Greg Mullavey in his persona. Morrison died in Morgantown, West Virginia in 1989.

The Nazi government of Germany recovered the the aluminum alloy frame of the Hindenberg, melted it down, and recast it asLuftwaffee fighter planes.

Thirty-three months later, they attacked Poland and began World War II.

No comments:

Post a Comment